Introduction

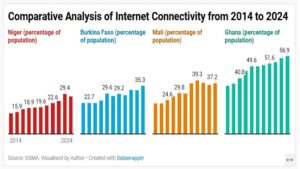

Over the past decade, Ghana has made significant progress in digital connectivity. The 2024 Mobile Connectivity Index indicates that 56.9 percent of Ghana’s population had access to the internet, compared with 37.2 percent for Mali, 35.3 percent for Burkina Faso, and 27.4 percent for Niger. As illustrated in Figure 1 below, between 2014 and 2024, Ghana’s internet connectivity increased from 35.4% to 56.9%, representing an improvement of 21.5 percentage points. This translates to a 60.7% relative increase over the ten-year period – higher than the gains recorded in Mali (15.0 points), Burkina Faso (12.8 points), and Niger (12.4 points). As of January 2025, around 24.3 million Ghanaians were internet users, accounting for approximately 69.9 % of the national population. Similarly, Ghana had 38.3 million mobile cellular connections for services like calls, texts, and internet. As the number of users and devices continues to increase, the speed and quality of connections are also improving – with 93.4% of mobile connections in Ghana now classified as ‘broadband’, meaning they operate on 3G, 4G, or 5G networks. With the expansion of mobile networks, increasing urbanization, and widespread use of affordable smartphones, more Ghanaians – especially young people, are actively engaging in the digital space.

Figure 1: Percentage of Population with Internet Access

Globally, there were 5.31 billion social media user identities as of April 2025 – roughly 64.7 % of the world’s population. As of January 2025, the number of active social media user identities in Ghana stood at about 7.95 million, representing around 22.9 % of the population, or 32.7 % of all internet users. Youth are the most active online demographic, engaging with digital content for entertainment, politics, religion, sports among others. Platforms such as WhatsApp, Facebook, TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube dominate the digital landscape in Ghana. These services enable users to connect, express themselves, and access information. This development has created new avenues for learning, entrepreneurship, civic participation, and social connection.

While this indicates increased digital empowerment, it also exposes users, especially youth to misinformation, hate speech, and in some instances, extremist content. Terrorists exploit these same spaces to push narratives around injustice, religious duty, or resistance. Extremist groups across West Africa such as Islamic State of West Africa Province (ISWAP) and Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) are leveraging social media and messaging platforms to promote violence, recruit followers, and spread radical ideologies. While Ghana has not yet experienced the scale of online radicalization seen in parts of the Sahel, its rising digital exposure and youthful population, coupled with socio-economic pressures, creates conditions of vulnerability. Consequently, in September 2021, the National Security of Ghana arrested 33 suspects at Nambahala, in the Northern Region who were believed to have links with terrorist organizations in Burkina Faso and Mali. However, a key concern is the limited digital literacy among many users, inhibiting their ability to evaluate content credibility and recognizing manipulative messaging. The limited public understanding of the drivers, strategies, and implications of online terrorism, coupled with the country’s history of protracted chieftaincy conflicts, and geographic proximity to volatile neighbouring countries like Burkina Faso, underscore the urgency for awareness and preventive policy measures.

This article explores the intersection between Ghana’s expanding digital access and the evolving threat of extremist propaganda online and how extremist groups exploit digital platforms to radicalize and recruit young people. It also highlights government and civil society responses and provides pragmatic recommendations for key stakeholders to build more resilient and secure digital environment.

Extremist Messaging and Online Strategy

Extremist groups operating in the Sahel and other parts of West Africa such as the ISWAP and JNIM are increasingly leveraging digital platforms as key tools to spread their ideology, justify violence, and recruit followers. These organizations exploit poor digital literacy, socio-political grievances, and economic marginalization particularly among the youth, to extend their influence beyond conflict zones. They disseminate their propaganda through both encrypted applications like Telegram and WhatsApp and more open platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram. These platforms are a go-to because of their massive youth user base, low barriers to content creation, and powerful algorithms that can amplify sensational or emotionally charged content.

The content shared by these groups is often strategically crafted to evoke feelings of injustice, abandonment, and religious duty. The narratives typically emphasize government corruption, state failure, and the promise of dignity, belonging, or divine reward through resistance. Research by the International Centre for the Study of Radicalization (ICSR) shows that extremist media increasingly mimics the aesthetics of mainstream content by using high-resolution videos, drone footage, nasheeds (Islamic chants), and even storytelling formats that appeal to younger audiences online.

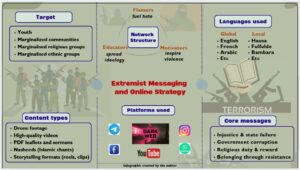

Figure 2: Extremist Groups’ Modus Operandi

Source: Authors

From Figure 2 above, extremist propaganda ecosystem operates on two interlinked levels: global and local. Extremist organizations targeting global audience produce highly polished content in Arabic, French, and English to reach a dispersed international audience. Locally, they target specific linguistic and cultural communities using Fulfulde, Hausa, Bambara, and other regional languages. These grassroots campaigns often use low-budget videos, audio sermons, and PDF leaflets circulated through informal networks like WhatsApp groups, making detection and counter-messaging difficult due to linguistic diversity and community-level buy-in of such propagandas. The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) stands out for its advanced digital strategy. Unlike Boko Haram or al-Shabaab, ISIL operates across a wider array of platforms including Facebook, Twitter (X), YouTube, WhatsApp, and Telegram. While Twitter was initially their preferred channel, the group shifted to Telegram and dark web as platform moderation intensified. By 2022, ISWAP was reportedly operating more than fifty (50) Telegram and Facebook accounts to coordinate their dissemination and recruitment agenda.

The terrorist groups often structure their online networks like digital ecosystems: with ‘educators’ who promote ideology, ‘motivators’ who inspire violence, and ‘flamers’ who provoke hostility and encourage fundraising. Such decentralised models help them to sustain their movements by adapting quickly to shutdowns or censorship. The spread of extremist content online has been likened to epidemiological contagion, where algorithm amplification allows messages to go viral within niche communities, increasing visibility and engagement exponentially. Although Ghana has not experienced the same intensity of digital radicalization as some neighbouring states like Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, the growing threat is concerning as the drivers of radicalization already exist.

Ghanaian Youth: Victims or Perpetrators of Radicalization?

In a 2023 UNDP assessment, youth unemployment was the leading driver of vulnerability to violent extremism in northern Ghana as national unemployment rate among 15–24-year-olds was 32.8%, with Upper East at 39%, Savannah at 38.2%, and North East at 34.7%. Online extremist recruiters continue to target vulnerable youth, particularly those battling with poor job prospects, limited education, and social exclusion in Ghana’s northern regions, which are also geographically close to extremist zones. Many near-recruit victims report first coming across extremist ideas through social media or messaging apps, where they were drawn in gradually – beginning with general religious or political content before progressing to more radical messages. Amin, a 21-year-old senior high school graduate from the northern region of Ghana recounted nearly joining IS after he was contacted online by an Algerian recruiter.

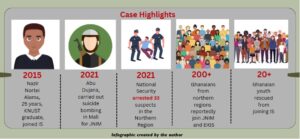

Extremist groups are exploiting digital platforms such as WhatsApp, Facebook, Telegram, and YouTube to reach Ghanaian youth with propaganda that frames injustice, religious obligation, and social identity narratives. A 2017 UNDP-RAND report identified these platforms as key venues for radicalization across Africa. Illustration in Figure 3 below highlights some cases recorded over the years in Ghana and beyond, involving Ghanaian youth. In 2015, Mohammad Nazir Nortei Alema, a 25-year-old geography graduate from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), joined and confirmed his allegiance to the Islamic State (IS) after being radicalized online. His case shocked the nation and underscored the dangerous appeal of online propaganda, even to the educated youth.

Similarly, security analysts reported that over two hundred (200) Ghanaians from northern regions have been recruited into extremist group affiliates such as the Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (EIGS) since 2015, often returning as religious propagators in their local communities. In June 2021, Abu Dujana, Ghanaian, carried out a suicide bombing near a French camp in Mali for JNIM, after urging an uprising against the Ghanaian government in a recorded video.

Figure 3: Case Highlights

Source: Authors

The terrorist groups also leverage Artificial Intelligence (AI) automation to spread media contents in their radicalization and recruitment agenda. Beyond direct recruitment, algorithms on social media platforms may inadvertently promote extremist content with ideological inclinations to users. This algorithmic reinforcement, coupled with emotional vulnerability, poses risks to youth lacking digital literacy. On the positive side, early prevention efforts have yielded tangible results. The West Africa Centre for Counter-Extremism (WACCE) in Ghana reported rescuing at least twenty (20) Ghanaian youth from joining IS fighters, many of whom were radicalized online.

Ghana’s Response to Online Radicalization

Government Measures

The government through the mandated state institutions and agencies, has undertaken various initiatives to prevent and respond to online radicalizations. Some of these initiatives are highlighted below:

- Cybersecurity Legislation: The Cybersecurity Act, 2020 (Act 1038) established the Cyber Security Authority (CSA) to regulate digital activities, protect critical information infrastructure, and coordinate national responses to online threats. This legal framework enables the state to monitor and address harmful and extremist digital content.

- Intelligence Coordination: The National Counter-Terrorism Fusion Centre (NCTFC) leads counter-extremism efforts with support from a Fusion Operations Centre, which facilitates intelligence sharing across agencies.

- Public Awareness Initiatives: The ”See Something, Say Something” campaign, launched in 2021, promotes public vigilance and encourages citizens to report suspicious behavior including online radicalization as a preventive measure. The CSA has also been raising awareness about online radicalization and other forms of cyber security threats.

- Regional Collaboration through the Accra Initiative: Ghana is a founding member of the Accra Initiative (2017), a multilateral effort with Burkina Faso, Benin, Togo, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, and Niger aimed at combating cross-border crimes and terrorism through joint operations, intelligence sharing, and border security. Although the core activities of the Accra Initiative focused on joint operations, intelligence sharing and joint capacity building, it also worked with national institutions in charge of cyber security to counter the threat of online radicalization. However, since the latter part of 2024, the Accra Initiative has been inactive.

Ghana’s response to online radicalization has strengthened national resilience through a robust legal framework, improved intelligence coordination, and public awareness campaigns that empower citizens to identify and report extremist activities. Additionally, regional collaboration has enhanced cross-border intelligence sharing and cybersecurity cooperation, bolstering Ghana’s capacity to prevent and respond to digital extremism.

Civil Society Efforts

Civil Society Organisations have also implemented several programmes as part of the collective efforts to prevent violent extremism and online radicalizations. Some of these programmes by WANEP-Ghana, STAR-Ghana Foundation, Penplusbytes and WACCE are briefly presented below:

- Digital Literacy & Counter-Extremism Education: The STAR-Ghana Foundation, through its Building Resilience Against Violent Extremism (BRAVE) initiative, trained over two hundred (200) youth in digital literacy and critical thinking across northern Ghana, alongside training of thirty-one (31) local facilitators on digital resilience to online radical messaging.

- Community-Based Peacebuilding & Early Warning: WANEP-Ghana, through its Conflict Early Warning and Response Mechanism (CEWER), systematically engages communities including youth and women to identify escalating tensions and promote preventive dialogue. This local approach helps mitigate extremist influence and social fragmentation.

- Media Literacy & Public Awareness Campaigns: Penplusbytes has implemented media literacy training targeting youth and women in the Oti, Volta and Eastern regions. These initiatives focus on disinformation, online safety, and the detection of extremist narratives.

- Localization & Peace Ambassador Training: The West Africa Centre for Counter-Extremism (WACCE) has also trained over nine thousand six hundred (9,600) ‘peace ambassadors’ and reportedly intervened in more than twenty-three (23) recruitment cases involving Ghanaians, showcasing the tangible impact of community-level engagement.

Civil society interventions have built community resilience by equipping youth, women, and local facilitators with digital literacy, media literacy, and critical thinking skills to resist extremist narratives online. Through peace ambassador training, early warning systems, and localized awareness campaigns, these initiatives have strengthened grassroots vigilance and contributed to disrupting the recruitment efforts by violent extremist groups.

Gaps and Limitations

Despite government and civil society efforts, some gaps remain in addressing online radicalization. Poor coordination among stakeholders has led to duplication and inefficiencies, while the private sector, especially internet service providers (ISPs) and social media platforms, remains underutilized despite its crucial role in content regulation. Also, most interventions are concentrated in urban centers, leaving rural and border communities with limited support, while weak public trust in state-led efforts, particularly in border regions, undermines community cooperation. Additionally, many initiatives suffer from short-term donor funding and insufficient national budget allocation. Lastly, the lack of localized research and data further hinders targeted responses, and policymakers also face the challenge of balancing national security with civil liberties, including freedom of expression and privacy in digital spaces.

Preventing Online Radicalization

Tackling online radicalization in Ghana requires coordinated action across government, civil society, technology actors, and regional partners. Responsible government agencies and ministries need to integrate media and civic literacy into school curricula, invest in cybersecurity infrastructure, and strengthen legal frameworks and interagency coordination. Civil society organisations are also encouraged to expand digital literacy and counter-narrative campaigns, localize interventions in high-risk areas, and engage influencers and religious leaders to amplify positive messaging. Technology companies should enhance content moderation, develop local-language monitoring tools, support digital safety campaigns, and ensure greater transparency in data sharing, while regional partners such as ECOWAS is urged to deepen cross-border intelligence sharing and capacity building.

Although extremist recruitment online remains limited in Ghana, the growing digital engagement of youth, combined with socio-economic vulnerabilities and regional insecurity, underscores the urgency for action. Ghana has made progress through legal reforms, multi-agency coordination, and grassroots initiatives, but gaps exist in rural outreach, institutional capacity, and private sector involvement. Moving forward, proactive strategies that emphasize prevention, digital resilience, and inclusion will be key to transforming digital spaces into tools for empowerment and safeguarding Ghana’s relative peace.

Authors

Anthony Caid Gbemapu,

Research Intern, WANEP

Dr. Festus Kofi Aubyn

Regional Coordinator, Research and Capacity Building, WANEP

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of WANEP. While every attempt has been made to ensure that the information published is accurate, no responsibility or liability is accepted for any loss, damage or disruptions caused by errors or omissions whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, or any other cause.

Comments